If you want to read a profile of some pretty amazing companies, go to www.henokiens.com. This is a newly redesigned website of the Henokiens International Association of Bicentenary Family Companies. Currently the Henokiens Association consists of 44 members from Europe and Japan. Though there are very few U.S. companies over 200 years old that are still being run by members of the founding family (three, by my count), my hope is that soon one of them will be added to this list of current Henokien members:

AMARELLI (1731)

AKAFUKU (1707)

AE KöCHERT (1814)

AUGUSTEA (1629)

BANQUE HOTTINGUER (1786)

BANQUE LOMBARD ODIER & CIE SA (1796)

BANQUE PICTET & CIE SA (1805)

BAROVIER & TOSO (1295)

CARTIERA MANTOVANA (1615)

C.HOARE & CO (1672)

CONFETTI MARIO PELINO (1783)

DE KUYPER ROYAL DISTILLERS (1695)

DESCOURS & CABAUD (1782)

DIETEREN (1805)

DITTA BORDOLO NARDINI (1779)

EDITIONS HENRY LEMOINE (1772)

ETABLISSEMENTS PEUGEOT FRERES (1810)

FABBRICA D'ARMI PIETRO BERETTA (1526)

FRATELLI PIACENZA (1733)

FRIED. SCHWARZE (1664)

GEBR. SCHOELLER ANKER (1733)

GEKKEIKAN (1637)

GARBELLOTTO (1775)

GUERRIERI RIZZARDI (1678)

HOSHI (717)

HUGEL & FILS (1639)

JEAN ROZE (1756)

J.D. NEUHAUS (1745)

LANIFICIO G.B. CONTE (1757)

LES FILS DREYFUS & CIE SA (1813)

LOUIS LATOUR (1797)

MELLERIO DITS MELLER (1613)

MöLLERGROUP (1730)

MONZINO (1750)

OKAYA (1669)

POLLET (1763)

REVOL (1768)

SFCO (ANCIENNE MAISON GRADIS) (1685)

STABILIMENTO COLBACHINI (1745)

THIERCELIN (1809)

TORAYA (1600)

VIELLARD MIGEON & CIE (1796)

VAN EEGHEN GROUP (1662)

VITALE BARBERIS CANONICO (1663)

Wednesday, October 29, 2014

Wednesday, October 22, 2014

I'm A Long-term Employee, But Will You Love Me Tomorrow?

Building relationships with employees so they stay with the firm for a long time was consistently listed as a key longevity success factor by 100-year-old companies. They clearly believe it is a differentiating factor. It may be important, but it does not appear to be statistically significant when compared to philosophies reported by younger companies.

In our theoretical model of corporate longevity built from a number of case studies of old companies in both the U.S. and Japan, developing and retaining employees for the long term was one of the key factors. This importance was confirmed in surveys of old companies in both countries through answers to items dealing with efforts to retain employees and investments in training and developing employees. However, when testing the longevity model with young companies, they also indicated these things were important - though to a lesser extent than old companies, it was not a statistically significant difference. The only statistically significant item was the effort old companies take to teach employees about company history and traditions (likely because younger companies don't yet have much history or many traditions).

Possible explanations for the lack of significant difference in old and young companies self-reported behavior toward employees is that young companies realize retaining well-trained employees will be of great benefit to their business. Another possibility is that younger companies report intending to operate this way, but have not yet been tested as to whether they will actually keep employees on the payroll during tough times the way the older companies have actually done. Either way, it is clear that companies surviving for over 100 years believe long-term relationships with employees is a very important factor in their success.

Thursday, October 16, 2014

When It Comes To Change, Slow and Steady Wins the Race for Old Companies

Yes, old companies change and even innovate - they wouldn't have survived for over 100 years if they didn't. However, my research shows that the change process they use is quite different than that used by younger companies. Many might say they are too slow to change, but in the long run this seems to work to their advantage.

In his book The Living Company Arie de Gues explores behaviors of very large, very old companies. He says these companies are tolerant of "experiments on the edges," meaning corporate headquarters doesn't try to control or drive all the change within the firm. When one of the "experiments" proves to have value, then it can be implemented on a wider basis. This idea is similar to Peter Sims idea of "little bets" explained in his book Little Bets: How Breakthrough Ideas Emerge from Small Discoveries. In a recent article on corporate longevity in the McKinsley Quarterly former managing director Ian Davis observes: "A company that learns to adapt and change to meet market demands avoids not just the trauma of decline or an unwanted change of ownership but also very real transaction and disruption costs."

The vast majority of 100-year old companies are small to medium-sized firms that may not have a lot of room for experimenting on the edges or the capacity to support many little bets. So how do they go about innovating and changing? Many have different products from when they began and some are in completely different industries. Those that have stayed with their core product or service have still had to adapt to quantum changes in technology, global competition, vastly changing social and cultural mores over the last century. First, they constantly seek small, incremental improvements and adaptations. Second, they keep abreast of trends both within and external to their industry. Then, when it is determined that major change is needed, they take their time to carefully plan and implement the change.

My research indicates that old companies take a significantly longer time to plan a major change than do younger firms. The reason they take time when making moving the company in a new direction is that they want to bring their constituents along with them, so they make the effort to explain the need for change to employees, suppliers, and customers in order to convince them of the necessity for the new approach. In the process of explaining the need for change, the leaders are mindful of honoring all that was good about the past even though that may not be what is needed for the future. Leaders also make clear that, though what they do as a company - or the the way that they do it - may change, the core values of the firm will not change.

Because old companies take time to make major change, the casual observer often may not even notice that they are changing. Perhaps this is why so many people think of old companies as dinosaurs - watching the fast development of entrepreneurial firms is far more exciting. Well, the old companies may be slow-moving, but they definitely are not dinosaurs. And old companies may not be as exciting as new start-ups, but many more of them will still be around decades from now. To once again quote Ian Davis: "Survival is the ultimate performance measure."

The vast majority of 100-year old companies are small to medium-sized firms that may not have a lot of room for experimenting on the edges or the capacity to support many little bets. So how do they go about innovating and changing? Many have different products from when they began and some are in completely different industries. Those that have stayed with their core product or service have still had to adapt to quantum changes in technology, global competition, vastly changing social and cultural mores over the last century. First, they constantly seek small, incremental improvements and adaptations. Second, they keep abreast of trends both within and external to their industry. Then, when it is determined that major change is needed, they take their time to carefully plan and implement the change.

My research indicates that old companies take a significantly longer time to plan a major change than do younger firms. The reason they take time when making moving the company in a new direction is that they want to bring their constituents along with them, so they make the effort to explain the need for change to employees, suppliers, and customers in order to convince them of the necessity for the new approach. In the process of explaining the need for change, the leaders are mindful of honoring all that was good about the past even though that may not be what is needed for the future. Leaders also make clear that, though what they do as a company - or the the way that they do it - may change, the core values of the firm will not change.

Because old companies take time to make major change, the casual observer often may not even notice that they are changing. Perhaps this is why so many people think of old companies as dinosaurs - watching the fast development of entrepreneurial firms is far more exciting. Well, the old companies may be slow-moving, but they definitely are not dinosaurs. And old companies may not be as exciting as new start-ups, but many more of them will still be around decades from now. To once again quote Ian Davis: "Survival is the ultimate performance measure."

Tuesday, October 14, 2014

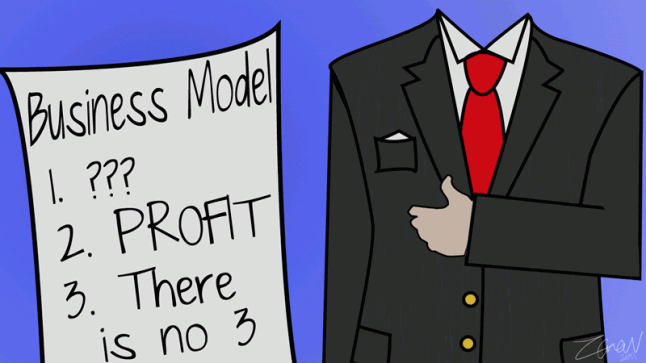

The Profit Paradox

I just returned from the Innovation Institute's Global Business Conference in Dubrovnik, Croatia where my presentation on the "survival" strategies of 100-year-old companies received a great response. (Dubrovnik is a gorgeous city, by the way, and I highly recommend both the venue and the conference.) One of the practices of old companies that received the interest of the conference attendees was the tendency for these companies to look at profit as the necessary fuel to keep their companies operating rather than as the goal or purpose of their business. Don't get me wrong - these companies are profitable; they wouldn't have survived for over 100 years if they weren't. And if they have to choose between profit and growth, they will choose profit. They just don't confuse needing to be profitable with the purpose of their business.

Corporate mission statements are very popular today and you can see them on almost every firm's website. These old companies have been talking about the purpose of their business in "missional" terms for decades, though they might not call it a Mission Statement. Whether it's to make great places to work (office furniture manufacturer), enhance human life (pharmaceutical company), or provide a bit of sunshine to every customer's day (candy store), the purpose of these old companies is clear and meaningful. They talk about their purpose all the time - with employees, with customers, with suppliers, their local community, academic researchers, and pretty much anyone who will listen. They love what they do and it shows. Their mission statement is not just words developed for their website because some management consultant told them they needed one. The mission of these old companies is real, and it is what has driven them to success for over a century.

The profit paradox is this: though these companies do not talk about maximizing profit as their goal or purpose (many don't really like to talk about it much at all), they are very profitable firms. In Japan (where my research partner was able to obtain profitability data, even from small privately-owned firms) companies over 100 years old were twice as profitable as the average Japanese firm. I have not been able to obtain such data from U.S. companies, but I suspect they are also more profitable than average. This is what has enabled them to weather tough times to survive for over 100 years. They don't focus on profit as the purpose for being in business, yet they are very profitable. As one CEO reminded me, profit is the result of doing well what they do as a company, not their goal.

Over the next month I will be posting other behaviors/strategies/principles exhibited by members of the corporate century club. These are statistically significant, cross-cultural behaviors based on ten years of research in both Japan and the United States. I hope you find this information as interesting as do I.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)